This book is not for the faint of heart.

This book is not for the faint of heart.

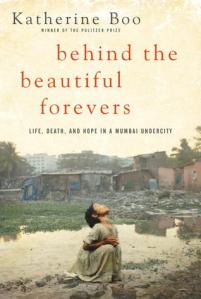

It is an unflinching look at unsettling poverty. More specifically, the story’s focus is on Annawadi, a slum that sits on the edge of the Mumbai airport and several luxury hotels. Even though India is starting to prosper, Annawadi and its residents are stuck in unfathomable conditions. Lives are overshadowed by incessant hunger, political corruption, and the fact that life expectancy in Mumbai is seven years shorter than that of the rest of the nation.

On more than one occasion, I had to remind myself that this was non-fiction. Perhaps it was a coping mechanism, because how, in this day and age, could there be an enormous community that shares a public toilet? How could people have to wait in line at a single tap when they need water? When people are hungry, should they not have the opportunity to feed themselves and their families? A full belly should not be a luxury that is perpetually out of reach.

The miracle of Katherine Boo’s narrative is that so many of Annawadi’s people never give up hope. Boo spent over three years observing residents of this makeshift slum, and she fixed her attention on a handful of families whose lives were intertwined. One of the things that made these people different from one another was the method they each employed to elevate their situations. Some picked trash and resold it to recyclers. Some turned to prostitution. Some taught. Some dabbled in “politics.”

Abdul, a Muslim teen who worked tirelessly as a “trash picker,” is a person you will not soon forget. Not only does Abdul’s heart steal the reader’s, but his steady resolve provides inspiration.

With this take, added to savings from the previous year, his parents would now make their first deposit on a twelve-hundred-square-foot plot of land in a quiet community in Vasai, just outside the city, where Muslim recyclers predominated. If life and global markets kept going their way, they would soon be landowners, not squatters, in a place where Abdul was pretty sure no one would call him garbage.

When Abdul is unjustly accused of a crime he did not commit, you will be angered at first, and then horrified when his family cannot find the money to purchase his freedom. No spoilers here; you’ll have to get a copy to find out if justice prevails.

The purchasing of his innocence was just one example of the area’s wayward practices. Police Officers, doctors, social workers, slumlords, and the like were not only receptive to bribes, they fully anticipated them. Hence, the book’s undercurrent of corruption in a land that was “sensitive” about its slums, but not willing to do anything about them. On the contrary, more often than not, the slums provided ample opportunity for exploitation.

The Indian criminal justice system was a market like garbage, Abdul now understood. Innocence and guilt could be bought and sold like a kilo of polyurethane bags.

The system is heartbreaking.

Boo reports that the Mumbai airport’s perimeter housed “roughly ninety thousand families” who were “squatting.” That certainly takes a moment to digest. She also notes that “despite economic growth, more than half of Greater Mumbai’s citizenry lived in makeshift housing.”

It’s beyond comprehension that one nation houses one third of the world’s poverty.

As she sheds light on the lives of a few families, Boo tells their stories with great wisdom and compassion. Behind The Beautiful Forevers is a remarkable accomplishment, because it offers an enveloping read while simultaneously educating the reader about a great injustice. This book is as gripping as it is necessary. 4 stars.

2 Comments

I just sent this back to the library unread! There was a hold list, so it couldn’t be renewed. I’m putting my name back on the list.

I’m so glad! I think you’ll be happy that you did.